But housing is a human right, isn’t it?

The interaction of various changes on housing markets has led to a volatile situation and made political control harder. Therefore, it is all the more important to clearly define objectives and in-struments.

At least, it is undisputed that housing is one of the important fundamental requirements for par-ticipation in societal life, providing the proverbial “roof over the head” and being an anchor for the organisation of personal life. However, the evaluation of housing provision is more than just a question of the simple existence of a house or flat. Rather quality of life is shaped by the neighbourhood and living conditions, which can also be understood as how well the house or flat can be adapted to the resident’s life situation. This connection was dramatically illustrated by Heinrich Zille, “You can slay a person with an axe, but you can also kill him with housing”. Only in very rare cases do current living conditions have any semblance to those of the late 19th Century. Yet housing policy has remained a central topic of social policy and it continues to tackle lack of housing, high rents and increasing property prices.

What is needed for a housing policy re-orientation?

It is expressed in the objective anchored in the 2022 Coalition Agreement to build 400,000 new homes each year. Even at the time the resolution was an ambitious objective since the COVID 19 pandemic had already led to building material supply shortages and cost increases in the construction industry. The situation was aggravated further by the end of a period of low interest rates and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since then, barely a week goes by in which the in-creasing difference between the number of homes built and the target is not mentioned in some form or other, or the current housing policy is not declared to have failed. At the same time, the list of suggestions or rather demands for housing policy re-orientation is growing. They cannot be discussed here in detail, but I think it is important to differentiate between long-term and short-term steps. Short-term measures to cushion the cost increases can be found, inter alia., in housing support programmes and property tendering by municipalities. However, these measures are extremely reliant on their respective budgets. Yet, on a long-term basis the de-mands seek to lower building standards (e.g., energy efficiency, accessibility and regulations from the building codes) and the quota of affordable homes, or to reduce/simplify land transfer tax. Many of the suggestions are by no means new, however the vigour with which they are presented is increasing because in the light of rental rates for the freely financed housing con-struction, calculated at between 17.50 and 20 euros per square metre (net base rent), new builds ultimately risk being unaffordable for many households.

New build housing vs rents in housing stock

The current situation on the housing markets should not be read as linear consequences of the developments. Rather the culmination of shock events represent exceptional circumstances, which should also be treated as such. “We are experiencing a cyclical moment of reset, similar to the late 1990s or after the financial crisis” (Leykam, 2023). The sustained period of low inter-est caused property (concrete gold) to gain a previously non-existent appeal as a form of in-vestment. The housing boom accelerated the establishment of property firms, which could only function in these special conditions and are now regarded as the faces of the crisis. Today, the purchase prices of properties are proving to be too high and are damaging the asset values of the companies. Altogether the period of low interest was not used enough to support innovation in the property sector, instead money was often drawn out of the housing stock.

Granting new builds a particularly high significance in housing policy instruments is based on the diagnosis that a majority of rental increases are a result of scarcity, also known as a landlords’ market. In contrast, the 2000’s saw a renters’ market in many cities meaning that the landlords could not demand any rent they chose. Constructing a surplus of housing and in doing so relax-ing the market did not appear to be a realistic scenario in the aforementioned framework condi-tions. However, I would like to refer to a different phenomena: when high initial costs in housing construction is bemoaned, then a type of cost rent is calculated, whereas rent pricing is other-wise based on the market rent. It does not necessarily reflect the costs, but derives the rent from how much the housing seekers are prepared to pay.

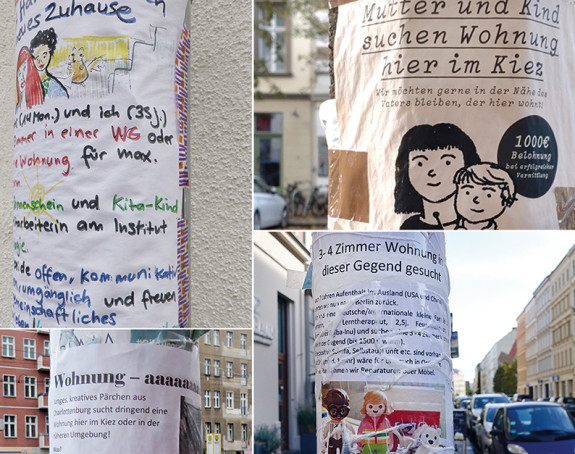

The rent break agreed in 2015 attempts to limit these options, nevertheless, the rents for the housing on offer continues to diverge away from the rents of existing tenants, for whom the rental laws largely provide protective mechanisms. As a result, the domestic migration rate is sinking. In 2004, it was still 11.4 percent in Berlin, whereas in 2020 it was just 6.9 percent, thus 122,000 relocations did not happen in 2020 (Investitionsbank Berlin, 2022). Since the adaptation of living conditions is connected with considerably more housing costs, many renters remain in their current housing even though it potentially no longer meets their requirements because it is now too large or too small, or is too far from their place of work, etc. The consequence of this lock-in effect is that especially in prospering agglomerations the accessibility to the housing market has become worse over the past decade.

The housing market: challenges and solutions

In order to counter these developments, initiatives for house and flat swaps have been launched in many cities but to date, they have not had any significant effect. In contrast, other sugges-tions (Ochs, 2023; Sebastian, 2021) call for the level of the existing tenant’s rent to be raised so they meet the rents of the housing on offer or call for regulations to be reduced. In doing so, there would be less incentive to remain in a too big home and “blocked” residential space would be returned to the housing market. Behind this assertion is the on average increasing living area per head, which nevertheless is substantially lower for renters in large towns and cities than for owners or also for renters in rural areas. The second part of the argument is based on the fact that the rents of existing tenants is held at an “artificially” low level and therefore, the owners are effectively being taxed. In turn, the market rent, which does not exclusively result from the ac-tual costs but also from the scarcity of housing and general societal investments in neighbour-hood and infrastructure, serves as the reference value.

For existing tenants in addition to private reasons, e.g., change in family size or divorce etc., there are also external factors which make moving house unavoidable, e.g., the registration of the owners personal need for the property, an unaffordable rent increase or if the building has to make way for a replacement new build (Thielmann & Schloz, 2023). The line of separation be-tween housing users and housing seekers is therefore by no means impermeable and the inse-curity has an effect that goes deep into the urban society, “in a freely revolving city like Munich with its exponentially rising land, property and rental prices, housing associations are one of the few emergency exits to escape the merciless market” (Krass et al., 2023).

Housing is a human right

The pattern of thought that interprets high rents for everyone as an instrument of a “fairer,” more relaxed housing market also includes support for the “truly” needy, who are supported with housing benefit in a precisely targeted manner. However, ultimately rent becoming an increas-ingly larger proportion of household income as well as the public transfer of benefits can also be interpreted as “the destruction of purchase power”. The money is not available for other ex-penses or purposes. The human right to housing needs more than emergency exits and it is high time that an alternative distribution mechanism to simply changing the price is developed.